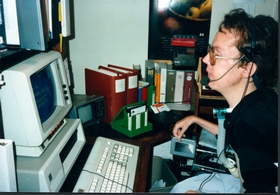

I am a quadriplegic. I have muscular dystrophy. In February 1984, I suffered a respiratory arrest. I had just completed a tough semester and was starting another. This period was very difficult because it seemed as though, no matter how much sleep I got at night; I was exhausted every morning. Apparently, the arrest was coming on for a month, but I wasn’t aware of how serious the sleepiness was.

One day, my mom decided to let me sleep in because I was so tired; she planned to do some shopping while my grandmother stayed with me. Mom told me later that just as she was closing the door, she had a feeling that something was not quite right with me. My mom discovered me. I was blue and barely breathing so she pushed the Medic-Alert box. The paramedics arrived about ten minutes later; they intubated me and rushed me to the hospital.

A day or two later, I woke up. The first thing I noticed was a room full of balloons and my family all around the bed. It was a strange but reassuring sight. I was wondering what was I doing here and why I couldn’t talk. My mouth was incredibly dry and my nose and throat were sore from being intubated. I became painfully aware of the importance of speech when I wasn’t able to communicate even the simplest of needs. I remained optimistic. After all, how long could this last?

We went through several different methods of communication. We tried charades; we tried going through every letter in the alphabet; and I tried using a list of commonly used phrases. Although these methods were adequate, they sure were maddening. I was intubated for a few days and I wasn’t exchanging gases adequately enough. It was decided that a tracheostomy was necessary. It was definitely not what I wanted.

A funny thing happened on the way to surgery, at least if you don’t really believe Dr. Welby. I was given a local and, after a few minutes, two doctors came up to the gurney. One of them was a short intern who needed to use a step stool just to reach me, which was bad enough, but then he started to make a horizontal incision as is done for children. Luckily, the other doctor was paying attention and stepped in and did the incision vertically and the tracheostomy was completed smoothly.

A friend, who had been trached a few months before, was kind enough to come by and offer some advice about living with a trach. I left the hospital on a hopeful note. When I got home, however, I became very depressed and angry because I wasn’t able to wean myself from the ventilator. I tried to plug my trach, but I just didn’t have the strength.

I’ve always felt that I was indestructible. Then my respiratory arrest shook me to my foundation. I felt betrayed, angry and bitter. How could this happen? What had I done to deserve this? I had accepted that I was not able to walk, I had accepted that I had lost arm strength after an operation to correct a curvature of my spine, but I felt that I couldn’t take any more. I became more and more withdrawn as it seemed my world had ended. I lost interest in everything-family, friends, even food and personal comfort. I had awful thoughts of suicide. Life became merely an existence that I had been imprisoned in.

“Even though I was sinking into an abyss of despair, something in me was not ready to give up. I said to myself, “Wait a minute! You’ve never given up this easily before and you’re not going to this time. There has to be a way around this problem.” These thoughts became my theme for three agonizing months.”

A couple of months went by before the idea came to me. One night, I noticed a valve in my ventilator circuit. This was a one-way valve designed to allow an extra breath to be taken between the inspiration and close on exhalation. All I needed was to take this valve and to adapt it to fit the hub of the inner cannula of my trach. My valve would allow me to breathe through the trach and then the air would be forced up through my vocal chords and nasal passages. I explained my idea to a psychologist I was seeing. She told a friend who knew Dr. Victor Passy.

I contacted Dr. Passy at UCI and told him of my idea. He was interested enough to invite me to his office to discuss my idea. When I arrived, Dr. Passy was a little surprised that I was a patient and not a doctor or an engineer. I showed him the valve and told him of my desire to help other trached patients. He seemed excited about its effectiveness, but then explained that I needed a way to adapt it to the trach. That night Dr. Passy told his wife, Patricia, about my visit. Having had previous business experience, she was very interested in the prospects of the valve. Patricia did some investigating and later contacted me with the results. I learned that over two million trach tubes are distributed a year and that trachs were not limited to just quads like myself. So we, Patricia and I, formed a corporation and went about the job of letting people know about my ideas for the valve.

Our prototype worked, but I found that it was difficult to use for long periods of time because the flap inside was made of rubber and was hard to move. Another problem was its appearance. It protruded too much from the trach and the red flap was unattractive. We experimented with different combinations of materials and designs until we found the right combination. One of our failures would have made a perfect duck call because it made a very loud QUACK! I discovered that I could sound like a woodcock or even a Canadian goose. Finally, we came up with a valve that was smooth with a relatively short protrusion and a light, easy to move diaphragm.

We took our valve on the road, so to speak, starting with a local meeting of otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat surgeons who specialize in airway and trachs). I’ve been to conventions before, but it feels a lot different on the other side of the table. Then we attended a meeting in Atlanta. This was my first trip on an airliner and my first big meeting. We had some literature made up and I had appeared in an ad in many magazines. I was interviewed by a few reporters and I even received a congratulatory letter from Dr. Robert Schuller. All this was fun and flattering, but the most rewarding aspect of the valve is that it has helped many people.

I learned many things from this experience. I learned that anger, if turned toward a problem rather than toward oneself or circumstances, can be overcome and God can work wonders. Indeed, just as I thought God had turned His back on me, He, in reality, gave me an incredible opportunity to help myself and others. Another important lesson is, that no matter how far you sink into despair, never shut out your loved ones because there is nothing more selfish than to cause pain to those who are there for you.

As corny and trite as it may sound, “In every rain cloud there is a silver lining.” This is absolutely true. Ask me, I know first hand.